Thick Authenticity New Media and Authentic Learning Review

Abstruse

Educational actuality occupies a strong position in higher didactics research and reform, building on the assumption that correspondence between college didactics learning environments and professional settings is a driver of student engagement and transfer of knowledge beyond academia. In this paper, we draw attention to an overlooked aspect of authenticity, namely the rhetorical piece of work teachers engage in to establish their learning environments equally authentic and pedagogically appropriate. We use the term "actuality work" to announce such rhetorical work. Cartoon on ethnography and critical discourse assay, we describe how two teachers engaged in authenticity piece of work through renegotiating professional and educational discourse in their projection-based technology course. This ideological project was facilitated by three discursive strategies: (1) deficitization of students and academia, (ii) naturalization of industry practices, and (3) polarization of the state of diplomacy in academia and in industry. Our findings suggest that authenticity piece of work is a double-edged sword: While authenticity work may serve to bolster the legitimacy that is ascribed to learning environments, it may also shut down opportunities for students to develop critical thinking about their profession and their teaching. Based on these findings, we hash out implications for teaching and propose a nascent research agenda for actuality work in higher education learning environments.

Introduction

Authenticity has become a ubiquitous concept in discussions about college education teaching and reform. The terms educational authenticity and, more normally, authentic learning are frequently used to criticize and move abroad from "decontextualized" forms of didactics in higher education (Andersson and Andersson 2005; Lüddecke 2016). The criticism leveled at decontextualized teaching is rooted in the ascertainment that students oftentimes neglect to see relevance in what they are learning and neglect to transfer knowledge to "real-world" settings (Barab and Duffy 2012; Perkins and Salomon 2012). Educational authenticity is understood as a solution to such problems.

The term "authenticity" is usually taken to hateful correspondence or connexion between learning environments in academia and professional environments beyond academia (Shaffer and Resnick 1999; Strobel et al. 2013). The basic assumption is that student date, professional identity development, and knowledge transfer are all better supported by learning environments that reflect "how knowledge is produced and communicated in professional settings" (Wald and Harland 2017, p. 753). Equally such, arguments concerning educational authenticity are specially salient in discussions of pedagogy in higher education programs aimed at specific professions (Bialystok 2017). Authenticity is sometimes alternatively conceptualized in line with educational philosophy and used to talk over properties and experiences of students and teachers as well every bit their means of beingness in the world (Kreber and Klampfleitner 2013; Ramezanzadeh et al. 2017). All the same, this paper is concerned specifically with the "correspondence view" of authenticity (Splitter 2009), which focuses on the qualities of learning environments and objects thereof.

A perusal of the extensive literature that has developed around this topic reveals 2 dominant theoretical perspectives on educational actuality. A large number of studies see authenticity primarily as an objective property of learning environments. These studies focus on how learning environments are designed in order to attain a loftier degree of correspondence or connection to "real" professional person practise (Jonassen et al. 2006; Newmann et al. 1996; Wedelin and Adawi 2015) and the affect of such learning environments on student learning (Chen et al. 2015; Hursen 2016; Radović et al. 2020). These design efforts often middle on how tasks, assessment, and physical as well as social contexts may be designed to reflect the conditions of professional settings (Gulikers et al. 2004; Strobel et al. 2013).

In stark contrast to such a theoretical perspective, other studies meet authenticity primarily every bit a subjective property of learning environments. These studies focus on how teachers and students perceive learning environments that are designed to be authentic (Gulikers et al. 2008; Nicaise et al. 2000; Wallin et al. 2017; Weninger 2018). In that location are ii main points of departure in these studies. Start, teachers and students do not necessarily agree on what may exist considered authentic, since "teachers are likely to have a unlike idea of what professional practise looks like than students practice" (Gulikers et al. 2008, p. 408). 2d, teachers and students practice not necessarily agree on whether information technology is pedagogically appropriate to model learning environments on professional exercise, as students may perceive this as "non-bookish, non-rigorous, time wasting and unnecessary to efficient learning" (Herrington et al. 2003, p.61). Therefore, from this perspective, the key to reaping the benefits of actuality is that students perceive learning environments every bit both authentic and pedagogically appropriate (McCune 2009; Roach et al. 2018; Stein et al. 2004) or at least "suspend" their atheism (Herrington et al. 2003). Otherwise, they will not participate wholeheartedly.

Recognizing such potential disagreements between teachers and students, diverse scholars accept called on teachers to win students over and eternalize the legitimacy of their learning environments through persuasion. Nosotros will employ the term authenticity piece of work (Peterson 2005) to refer to such projects, where "work" denotes continuous efforts made by actors to found sure social facts well-nigh themselves or about the globe (cf. identity piece of work; Barton et al. 2013). In our usage, authenticity work encompasses the rhetorical work teachers appoint in to establish their learning environments as authentic and pedagogically advisable. Petraglia (1998) places importance on authenticity work when asserting that "we demand to convince learners of a problem's authenticity" (p. 53). Similarly, Woolf and Quinn (2009) point towards the need for authenticity work when arguing that "instructors adopting this approach need to stress that one purpose of the course is to experience the sick-structure and ambiguity of the professional person exercise" (p. twoscore). Withal, despite such encouragement and despite calls for studies that "examine the impact of various factors contributing to students' perceptions of value and affect of different learning experiences" (Sutherland and Markauskaite 2012, p. 762), we could not find any studies directly examining teachers' authenticity work in a college education setting Footnote i.

With this paper, we aim to address the empirical void surrounding authenticity work in college instruction. The newspaper rests on ii theoretical assumptions, which shaped our research questions and design. First, in contrast to most previous studies on educational authenticity, nosotros take our theoretical point of departure in the view that actuality is a socially constructed property of learning environments rather than objective or subjective (Barab et al. 2000; Hung and Chen 2007; Wald and Harland 2017). That is, authenticity is attributed to learning environments in and through social interaction. Second, while authenticity is a term with potent positive overtones in education, nosotros recognize that authenticity "allude[southward] to inherent and implicit ideas of ability, realness, authority and, ultimately, of superiority" (Wald and Harland 2017, p. 752). Thus, we fence that fifty-fifty though authenticity work is undertaken with good intentions, it tin take unintended consequences. Chiefly, constructing certain practices as authentic may discourage disquisitional scrutiny and may also come at the expense of other practices that are simultaneously constructed equally inauthentic (Dishon 2020). This observation sparked our interest in exploring authenticity work from a disquisitional perspective, cartoon on the notions of discourse and ideology (Fairclough 1992).

We situated our study in the context of technology education, because actuality is a prominent concept in discussions of engineering education pedagogy and reform (Strobel et al. 2013) and since nosotros, working at a technical academy, have a particular involvement in researching and developing engineering science education. Further, nosotros focus our study on a project-based learning environment because project-based learning is strongly associated with actuality (Blumenfeld et al. 1991; Prince and Felder 2007). We use a methodological blend of ethnography and disquisitional discourse analysis (Krzyżanowski 2011), developing a "thick description" (Geertz 1973) of the authenticity work a pair of teachers engage in—as the central plank—in reforming their project-based class on software engineering science. In our analysis, we seek to address the post-obit research questions:

- (one).

What discursive strategies do the two teachers draw on to establish their learning environment equally authentic and pedagogically appropriate?

- (two).

What are the ideological consequences of their actuality work?

Nosotros believe that this assay can inform authenticity work in other disciplinary settings and in learning environments that are not project-based. Merely perhaps more importantly, insights from employing a disquisitional perspective tin "kick back" at taken-for-granted assumptions (Alvesson and Kärreman 2011) and invite both teachers and researchers to reconsider the status of educational authenticity every bit a key concept in higher instruction research and reform.

Methodology and methods

The nowadays study draws on 2 qualitative inquiry traditions—ethnography and critical discourse analysis—to explore authenticity work in higher instruction learning environments. Broadly stated, ethnographers are interested in gaining an in-depth understanding of what is "going on" in specific social settings—in terms of social interactions, behaviors, and norms—past observing and interacting with people in these settings over longer periods of time (Delamont 2012). By using observations in tandem with interviews, ethnographers are able to move beyond a sole focus on perceptions to reveal "social practices which are normally 'hidden' from the public gaze" (Reeves et al. 2013, p. 1365). Discourse analysts, on the other hand, are interested in elucidating how these social practices found and transform the social earth, analyzing practices in terms of soapbox—that is, patterned language use in a social setting (Gee 2014). A fundamental starting point for all discourse assay is that discourse serves a number of functions beyond merely transmitting information. Through discourse, subjects and objects are constructed, represented, connected, and given pregnant equally well as relative status (Gee 2014).

Inside the broad theoretical tradition of discourse analysis, critical soapbox analysis attends specifically to ideological processes in soapbox (Fairclough 1992; Gee 2014). An important unit of analysis in such work is the local social club of discourse—that is, the configuration of discourses drawn on in a certain social sphere—and its continuous renegotiation (Fairclough 1992). Local orders of soapbox often incorporate several competing discourses struggling for the same terrain, each contributing to the establishment of competing ways of understanding and organizing social activity (e.g., marketplace-oriented and social justice-oriented discourses of academia). When certain discourses achieve a dominant status, this implies that certain ideological relations become established (Chouliaraki and Fairclough 1999). Accordingly, the struggle for defining the order of discourse is a political struggle with ideological consequences.

Combining these two traditions, ethnography and critical discourse analysis, we aim to identify discursive strategies involved in actuality work. By the term "discursive strategies," we mean patterns of language use that serve to (re)construct the legitimacy or illegitimacy of certain practices or discourses (Vaara et al. 2006). Specifically, we aim to analyze how these discursive strategies contribute to establishing a sure society of discourse in the learning surround and what ideological consequences that follow. To this end, our ethnographic approach provided contextual richness through prolonged fieldwork and disquisitional discourse analysis provided a rigorous analytical frame focused on ideological processes in language (Atkinson et al. 2011; Cakewalk 2011). Before going deeper into belittling considerations, we first describe the empirical setting of our report and methods for data collection.

Empirical setting

The empirical setting for our written report was a project-based course in software applied science at a technical academy in Sweden. The course was given past two teachers, Jonas and Frank Footnote 2, both having a enquiry groundwork in software development and both as well having published papers on the topic of software engineering education. Jonas and Frank had taught the form together for a number of years when we came in contact with them. While Jonas was the formal examiner for the class and our first contact, Frank was the one teaching and supervising nigh of the sessions that we observed. The course was a role of a number of unlike study programs and thus involved students with somewhat different backgrounds. At the time of our study, 56 third-year available students—majoring in either software evolution or technology management and economics—were enrolled in the form.

The course revolved effectually a software engineering science projection in which students, in teams of five, were to conceive and develop software applications towards an external stakeholder organization. The purpose was to learn how to put programming skills into action and how to organize software engineering projects in line with principles of active software evolution (Dingsøyr et al. 2012) and SCRUM-methodology (Schwaber and Beedle 2002).

The form proceeded in three phases. During the first iii weeks, Jonas and Frank lectured on agile software development principles and SCRUM-methodology and had students endeavour information technology out through workshop exercises. The project assignment was introduced, and educatee teams were formed. In the 5 post-obit weeks, the projects were carried out. During these weeks, the students generally worked independently in their teams, with one joint session every calendar week where they consulted with the external stakeholder regarding the design of their applications and got supervision from Frank regarding the organization of their projects. At the end of the course, the students presented and demonstrated their finished application and wrote a project study.

Data drove

In order to study discursive strategies involved in Jonas and Frank's authenticity piece of work and potential ideological consequences, we employed a fieldwork approach to data collection, using classroom observations, formal interviews with teachers and students, and follow-upwards meetings with the teachers. The fieldwork was conducted by the first author, but nosotros retain the pronoun "we" in this section to reflect that the report was collaboratively designed.

We conducted in total 23 h of classroom observation. Here, we focused on how Jonas and Frank introduced the learning surroundings and how they elaborated their description as new activities were introduced. Further, we were interested in how students responded to and potentially rearticulated the teachers' manner of framing the course and projection and thus observed their questions and how they themselves talked near the learning environs. During these observations, we had recurring informal chats with both teachers and students to hear their thoughts about what was going on in the course. The observations were recorded in fieldnotes, with certain quotes transcribed verbatim.

In add-on, we conducted 15 interviews and meetings with teachers and students. Two interviews with Jonas and Frank were undertaken earlier the course started, in order to provide a first account of how they talked about their learning surroundings. In addition, we had 3 follow-up meetings with Jonas and Frank in the 2 years post-obit our fieldwork in order to hear them talk about new developments in their course and to discuss our emerging interpretations of what we had observed. In probing Jonas and Frank'south perspectives on the learning surroundings and events that transpired therein, we learned about their motives behind designing and framing the learning surround in a certain manner. X private interviews with students were undertaken just after the course had finished, where we asked students broadly about their experience of the learning environs and of specific situations we had observed. Students who were invited to take part in the interviews were sampled purposively across programs and project groups. All interviews were semi-structured in order to permit our respondents speak more often than not in their own terms. The interviews ranged between sixty and ninety min, were sound-recorded, and were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts and fieldnotes were analyzed in the original Swedish and quotes selected for the paper have been translated to English language. Participation in the study was voluntary, and nosotros informed our respondents that they could withdraw their participation at any time.

Data analysis

Like most information analysis involving qualitative fabric, our analysis procedure was a prolonged and iterative one (Miles and Huberman 1994). Our full general arroyo was to go back and forth betwixt shut readings of the empirical material and close readings of literature on educational authenticity while continuously formulating a clarification of Jonas and Frank's authenticity work. Aiming to produce a "thick" description (Geertz 1973), we moved gradually from scattered observations, seemingly pertaining to authenticity work, to constructing interpretations of what we found especially meaning. Evaluating our emerging interpretations, we scoured the empirical material for support and contradictory observations, assessed the relevance of our findings for the literature on educational authenticity, and reformulated and retested our assay.

Drawing on critical discourse analysis, a central element in this process was close-up analysis of specific instances of linguistic communication utilise (Gee 2014), in our case talk in the context of interviews and classroom interaction. First, we identified instances of language use where the nature, function, and/or status of the learning surround was described or negotiated. 2d, we analyzed these instances in terms of both linguistic content and structure (Gee 2014). In terms of content, we distinguished ii sets of discourses that were ofttimes fatigued on when talking about the learning environs (professional person and educational discourses), each including two competing discourse-orientations (a rigor orientation and a relevance orientation).

In terms of structure, nosotros identified discursive strategies employed by Jonas and Frank through looking for repeated patterns in their language use where subjects (e.thou., students, teachers, and professionals) and objects (e.thousand., learning activities, processes, and tools) were synthetic in such a way that the legitimacy of their learning surround was strengthened Footnote three. Farther, to investigate the ideological consequences of these discursive strategies, we analyzed students' language use in terms of intertextuality (Fairclough 1992), looking for acceptance of and/or challenges to the new order of discourse that Jonas and Frank'due south authenticity piece of work served to establish. When students reproduced elements of Jonas and Frank's discursive strategies—for example, through repeating exact phrases or arguments—we interpreted such correspondence as an indication that sure discourses had achieved a (temporarily) dominant status in the context of the form. Conversely, when students rearticulated—that is, rearranged discursive elements significantly—or rejected Jonas and Frank's discursive strategies, we saw this as an indication that the local order of soapbox was contested and that the status of private discourses was tenuous.

Findings

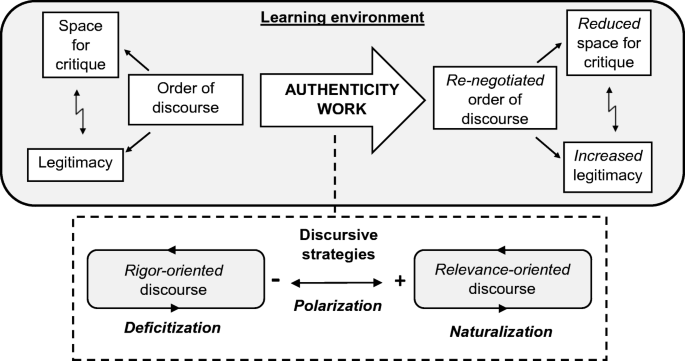

To facilitate an understanding of the different layers of findings that emerged from our analysis, nosotros begin past presenting a thumbnail sketch of our main findings (see Figure 1). A key finding is that the authenticity work Jonas and Frank engaged in can exist understood every bit an ideological projection, as their authenticity work served to found a different lodge of discourse in the learning environment. Specifically, this shift bolstered the legitimacy of the learning environment by strengthening the status of relevance-oriented professional and educational discourse at the expense of rigor-oriented discourse. Notably, Jonas and Frank's authenticity work involved three discursive strategies: (1) deficitization of students and of rigor-oriented soapbox, (two) naturalization of industry practices and of relevance-oriented discourse, and (iii) polarization of academia and manufacture as well as of rigor-oriented and relevance-oriented discourse. Elements of these discursive strategies were reproduced by near students at the end of the class, indicating that Jonas and Frank were largely successful in their actuality piece of work. A worrying finding, however, is that their authenticity work seemed to reduce the space for disquisitional reflection in the learning environs, endmost down opportunities for students to develop critical thinking well-nigh their profession and education.

Authenticity work was found to (1) constitute a dissimilar social club of discourse in the learning environment, (2) comprehend 3 discursive strategies—deficitization, naturalization, and polarization—enacted in renegotiating the orientation of both professional and educational soapbox, and (3) increment the legitimacy of the learning environs while simultaneously closing downwards opportunities for critical thinking

These findings are fleshed out and corroborated in three sections below, using illustrative extracts from the empirical cloth. The first department outlines the background to Jonas and Frank's authenticity work. This is followed by two sections illustrating the 3 discursive strategies that Jonas and Frank employed—first in renegotiating local professional person soapbox then in renegotiating local educational soapbox.

Responding to a legitimacy crisis with authenticity work

Jonas and Frank found themselves in a somewhat sticky situation as teachers. When undertaking the course project and when filling in the course evaluation, students recurrently questioned the legitimacy of the learning surround, voicing objections that often centered on the uncertainty and unpredictability that the project entailed. In contrast, Jonas and Frank took pride in their class, feeling that they had managed to organize a learning surround that corresponded to and connected students with engineering contexts beyond academia. Rather than stemming from an inappropriate design, Jonas and Frank deemed uncertainty and unpredictability to be integral to software engineering. Accordingly, although they continuously engaged in fine-tuning the course, they maintained that if the authenticity of the learning environment changed, and then the students would miss out on important lessons about "real" software engineering. Notwithstanding wanting to attend to the frustration that students voiced, Jonas and Frank turned their attention to irresolute the way in which students interpreted and participated in their learning environment.

Accordingly, much of what Jonas and Frank said almost their learning environment was recognizable as authenticity work, speaking both nigh its loftier degree of authenticity and the appropriateness of such a pedagogical arroyo. For instance, in the course introduction, Frank asserted both that the course featured "real bug," "existent tools," "real processes," "real stakeholders," and "real value" and that if the course would not accept had such a high degree of authenticity, "you wouldn't have had to face the well-nigh difficult questions." While such assertions were positioned as uncomplicated facts, the students did not, even so, automatically accept them. Thus, more than than simply communicating the rationale behind their learning environs, Jonas and Frank needed to locally renegotiate what was talked well-nigh as legitimate engineering practices and legitimate higher education practices. In soapbox belittling terms, they needed to establish a unlike social club of discourse in their learning environs.

Renegotiating local professional discourse through authenticity piece of work

In describing the order of professional discourse that they felt they were upwards confronting, Jonas and Frank held that software engineering science in college education is usually very rigor-oriented, and, therefore, so are their students:

We [university teachers] are teaching the students – at least on the technical programs – to think like hackers, much more than similar engineers. In that location is a difference, because a hacker is somebody who is very focused on technical details, on things like which database you use and how to elegantly implement that algorithm. […] [The students] are very much focused on the solutions. They want to be programmers, people who come up upwardly with an elegant technical solution. Merely they don't actually go this whole procedure thing, and stakeholder value and these kinds of things. That is non actually their principal concern. (Jonas, Interview)

Here, Jonas draws on a rigor-oriented discourse of technology—including terms such equally "technical details" and "elegant implementation"—to describe and criticize software engineering in the context of college education. In contrast, he privileges a relevance-oriented professional soapbox—including terms such every bit "stakeholder value"—constructing such discourse equally more useful for professionals. Because the projects Jonas and Frank had assigned their students were focused primarily on tailoring applications to the needs of an external stakeholder, rather than perfecting technical features, the legitimacy of their learning environment hinged on the status of relevance-oriented professional discourse in the local club of soapbox. Specifically, the learning surround's condition equally authentic—that is, corresponding to "real" engineering exercise—depended on the salience of relevance-oriented professional soapbox and the suppression of rigor-oriented professional soapbox.

In the same extract, we get a commencement glimpse of how Jonas and Frank's actuality work was facilitated by three discursive strategies: deficitization, naturalization, and polarization. In his statement, Jonas emphasizes the limitations of doing software engineering science in a technically rigorous fashion and claims that a focus on rigor is symptomatic to software applied science in the context of higher education. He thus deficitizes—that is, constructs as flawed—rigor-oriented professional discourse. Actors who draw on such discourse, including both teachers and students, are constructed as not "getting it" and as being "focused" on the wrong things. These presumed deficits are here constructed as the basis for students' objections to the grade design: the learning surroundings is non flawed; it is rather the students, the educational system, and the focus on technological rigor that is the problem. Further, Jonas naturalizes—that is, constructs every bit natural and superior—relevance-oriented professional soapbox: information technology is what "engineers" engage in and therefore what students and teachers should draw on. Finally, rigor and relevance are constructed as alien aims in applied science practice, cartoon on a distinction between relevance-oriented "engineers" on the one paw and rigor-oriented students and "hackers" on the other. Thus, rigor-oriented and relevance-oriented professional person discourse is polarized—that is, constructed as opposites.

These three discursive strategies entered the classroom through a recurring interaction pattern where Jonas and Frank corrected the way students talked about their projects, urging them to have up a more than relevance-oriented discourse. For example, in the following excerpt from ane of the introductory workshops, Jonas comments that the students are asking the wrong kind of questions about their projects, questions focused on databases. One of the students, Robin, speaking in line with a rigor-oriented professional person discourse, questions why they should not care about databases, while another educatee, Mika, aligns with Jonas in emphasizing relevance over rigor. Finally, Jonas reiterates his correction:

-

Excerpt one

| Jonas: | Many of you asked questions nigh databases – but that is not needed. |

|---|---|

| Robin: | In object-oriented programming you should exercise programs that are generic, and so that you can add functionality afterward. Adding a database, y'all could add together future functionality? |

| Jonas: | Interesting. [To class:] Comments? |

| Mika: | You lot should besides keep it unproblematic. |

| Jonas: | Yeah. […] A database is non creating value for the customer right at present; it is not requested at the moment. |

Most credible in this extract is the deficitization of rigor-oriented professional discourse, seen in Jonas' construction of questions regarding databases every bit "not needed" and "not requested." Instead, Jonas steers the official classroom talk towards "creating value for the customer," constructing relevance-oriented professional soapbox every bit more than important. Through the interaction, rigor- and relevance-oriented discourses of technology are over again polarized, synthetic as opposed rather than complementary.

In Extract one, we also get a get-go glimpse of how Jonas and Frank'south appetite to renegotiate the local social club of professional discourse jeopardized the infinite for critical reflection allowed in their learning surround. Although Robin offers a well-articulated bid at critical reflection on the relative claim of rigor and relevance in engineering practice, this window is relatively quickly closed by Jonas and Mika. We notice, for case, how Jonas' comment about whether databases are needed is formulated equally a argument rather than a question that is upwardly for critical give-and-take. Furthermore, recurrently correcting students and not taking upwards their critical reflections too serves to deficitize their disquisitional spoken language. Such a dynamic may maintain a teacher–student human relationship where teachers concur the authorization to outline what should be regarded as "existent" professional practices and students are to willingly accept these ideas.

From the interviews with students after the course, it was apparent that Jonas and Frank's attempts to locally renegotiate professional discourse had largely been successful. A majority of the students indeed described the project every bit "real" and corresponding to "the way that software development is actually washed." In corroborating these statements, they explicitly reproduced the discursive strategies Jonas and Frank had introduced to establish and maintain a new relative status of rigor- and relevance-oriented discourse. For instance, when Elin talked well-nigh what she had learned in the class, she stated the following:

We [students] take a tendency to go astray and do unnecessary things. Just is it really needed? […] Does anyone want that functionality? Does the code even demand to wait good or should nosotros focus on getting it working instead? (Elin, Interview)

Elin here uses both a rigor-oriented discourse—talking almost "code" that "looks good"—and a relevance-oriented discourse, asking whether "anyone want this?". Elin implies that she and her fellow students usually act in line with a rigor-oriented discourse. Through using rhetorical questions, she questions the value of such soapbox and through negative terms she constructs her and her fellow students' way of doing engineering as flawed ("we" "go astray" and "do unnecessary things"). In contrast, relevance-oriented discourse is constructed every bit important and "needed." The effect of Elin'southward statement is that rigor-oriented professional soapbox—as well as Elin herself—is deficitized while relevance-oriented professional discourse is naturalized. Embedded in such arguments were often positive comments about the course, indicating that the discursive strategies that Jonas and Frank introduced through their authenticity piece of work did indeed serve to bolster the legitimacy that was ascribed to the learning environment.

Still, students' reproduction of these discursive strategies also implies a lack of critical examination of the assumptions nearly engineering underpinning Jonas and Frank's authenticity work. Specifically, assumptions regarding for example what "real" engineers should care most (relevance), what is unnecessary for "real" engineers to focus on (technical rigor), and the land of diplomacy in academia vis-à-vis the state of affairs in manufacture (that they are unremarkably misaligned) seemed to fly nether the radar. In fact, none of the students we interviewed at the end of the course put along any significant rearticulation or critique of how professional do was portrayed in Jonas and Frank's authenticity work. As such, the legitimacy gained from their authenticity work seemed to have come at the expense of opportunities for disquisitional reflection.

Renegotiating local educational soapbox through authenticity work

Jonas and Frank'due south endeavour to establish a new order of educational discourse in their learning environment similarly boiled downwardly to a discursive and ideological shift from rigor to relevance. This renegotiation, however, seemed somewhat less successful. Describing the pre-established order of soapbox they felt they were up against, Jonas outlined the attempted shift from educational rigor to educational relevance:

We are trying to move away from classical lectures as much equally possible, and trying to move towards very applied, hands-on things you can do in the classroom […] Nosotros believe we reach the learning objectives much improve this way, but I remember some students just notice it plain annoying that they have to do something. […] [In other courses] the projects are defined by the teacher. The teacher says: "this year you are going to build this". But there is no connection to a stakeholder that actually derives value from it. It is called because information technology is a good example of... because y'all tin apply the content of the course to it. (Jonas, interview)

In this statement, Jonas draws on and naturalizes relevance-oriented educational discourse, constructing courses that shun "lectures" and instead "connect" to external "stakeholders" that can "derive value" from students' projects as pedagogically appropriate. Simultaneously, Jonas draws on and deficitizes rigor-oriented educational discourse, which centers on pedagogical structure and clarity. Here, this deficitization is accomplished through criticizing project courses building on tamed "skilful examples" aligned with the course "content." Jonas constructs relevance-oriented educational discourse every bit subjugated and not properly valued in higher teaching. Equally Jonas and Frank'due south learning surround centered on the idea of facilitating learning experiences that are readily transferrable to a professional setting, its status as pedagogically advisable hinged on the salience of relevance-oriented educational discourse in the local social club of discourse.

The same discursive strategies were employed in teacher–pupil interactions regarding the pedagogical claim of the learning environs. For case, in response to a educatee speaking to the limitations of unclear activities, Frank dedicated their pattern ideas in the following fashion when wrapping upward one of the introductory workshops:

-

Extract 2

| Frank: | Practice yous have any feedback? |

|---|---|

| Elliott: | I wish you would have given usa clearer directions for what we were supposed to do in the experiments. |

| Frank: | That was on purpose, so that you lot would experience being in a sprint, not knowing exactly what to practise and have to organize on your own. |

In this interaction, Elliott constructs what had happened in the workshop as "experiments" for which they had non received "clear directions," speaking in line with a rigor-oriented educational soapbox. In response, Frank emphasizes that the activities were designed to be relevant for the conditions of professional practice, specifically that of "being in a sprint"—a delimited phase where a software team implements planned edifice tasks—in which one cannot expect to know "exactly what to exercise." While a lack of clear directions can exist regarded as pedagogically inappropriate in rigor-oriented educational discourse, it is of import that engineering education reflects professional person weather—in line with relevance-oriented soapbox—and thus of import that students do not always become clear directions. Considering Elliott's statement is reinterpreted in this way and because the rigor-oriented soapbox in which it was articulated is non taken upwardly, the effect of Frank's argument is that relevance-oriented discourse is naturalized and rigor-oriented discourse is deficitized. Simultaneously, Elliott is positioned as not having considered a relevance-oriented interpretation of the workshop activities.

From the interviews with students at the end of the course, Jonas and Frank'south attempt to renegotiate the local order of educational discourse seemed somewhat inconclusive. The students drew recurrently on both relevance-oriented educational discourse—outlining how the course had felt "real" and that this was a positive thing—and rigor-oriented discourse, primarily in criticizing the ambiguity and unpredictability that the course had meant and in highlighting the stress and anxiety it had caused them. Their privileging of these discourses differed. Some students conspicuously reproduced the naturalization of relevance-oriented educational discourse and the deficitization of rigor-oriented educational discourse. For case, David fabricated many positive comments virtually Jonas and Frank'south learning environment and asserted that centering education on "fictitious" projects was "pure nonsense." Some other group of students ascribed equal legitimacy to both rigor- and relevance-oriented discourse. Olof, for example, asserted that the design of the learning surroundings "suited" the aims of the course but that educational rigor was important in courses where students are to acquire more "specific cognition," such as "JavaScript." A few students were more than skeptical. Simon, for instance, articulated a clear critique of Jonas and Frank'south relevance-oriented discourse:

It'due south all too common that teachers, already back in the science plan in high schoolhouse, justify unclear descriptions past proverb that yous will go a meliorate problem solver […] They shouldn't ever fall dorsum on that. I think it'south cowardly likewise. The goal can't ever be to make things unclear and then that nosotros get better at handling unclear situations. I don't think so. Sometimes I think there is value in the opportunity to dig deep technically too. […] We become damn good at managing the basic conditions that you'll come across in the get-go two weeks of any project. But we'll never be good at managing the rest of everything, because nosotros never accept time for that. (Simon, interview)

This argument from Simon illustrates an interesting exception to the full general lack of rearticulation of the assumptions underpinning Jonas and Frank'south authenticity work. Simon clearly rearticulates the condition of rigor-oriented and relevance-oriented educational soapbox in the local order of discourse. Commencement, he argues that it is "mutual" for teachers to talk most the value of "unclear descriptions." Through this statement, relevance-oriented discourse is constructed as pervasive rather than subjugated throughout the instruction system. Furthermore, Simon speaks almost such discourse in negative terms, equally something "all likewise" mutual that teachers "cowardly" "fall back on," and argues that it limits what students may learn from their studies. In contrast to Jonas and Frank's talk near relevance and rigor, the effect of Simon's statement is that relevance-oriented educational discourse is deficitized and rigor-oriented discourse is naturalized. Through rearticulating rather than reproducing Jonas and Frank's discursive strategies, Simon's statement illuminates and puts into question assumptions underpinning their authenticity work: Is higher pedagogy really also rigorous? Does educational rigor automatically make higher instruction learning environments less relevant for professional do? Simon'southward rare disquisitional reflection highlights that such assumptions adventure flight under the radar if teachers are overly successful in their actuality work.

To sum up, while Jonas and Frank seemed to have been able to convince the students that their learning surroundings corresponded to how "real" software engineering is done, they did non manage to convince all students that this authenticity was automatically pedagogically advisable. This meant that some students indeed continued to question the legitimacy of their learning environment. Nevertheless, this also meant that not all opportunities for critical reflection on different educational qualities were closed downwards.

Discussion

Using a blend of ethnography and critical discourse assay, we have explored authenticity work in a projection-based learning environment. In broad strokes, the analysis revealed that the teachers' authenticity piece of work (ane) established a dissimilar lodge of discourse in the learning environs and (two) encompassed iii discursive strategies that were enacted when renegotiating both professional and educational soapbox: deficitization, naturalization, and polarization (see Figure 1). The assay further revealed that authenticity work can be a double-edged sword, with both favorable and unfavorable ideological consequences: On the 1 paw, our findings support the hypothesis that authenticity work can bolster the legitimacy that is ascribed to learning environments. This may strengthen pupil participation. On the other manus, our findings besides suggest that authenticity work can jeopardize opportunities for critical reflection. This may stifle students' critical thinking nearly their future profession and their teaching.

Implications for theory and practice

In previous research on educational authenticity, students' perceptions have been considered central to why they practise not always participate wholeheartedly in learning environments that have been designed to be authentic (Gulikers et al. 2008; Herrington et al. 2003; Woolf and Quinn 2009). In line with such a conceptualization, teachers accept been encouraged to influence students' perceptions of learning environments through what we here accept termed authenticity work. Nosotros take issue with this dominant view. Our findings bespeak instead towards an alternative conceptualization: Legitimacy and student participation in learning environments hinge on the status of specific discourses in the local order of discourse. Authenticity piece of work can thus be understood equally an ideological project, involving a renegotiation of both professional discourse—establishing the learning environment as authentic—and educational soapbox, establishing the learning surroundings every bit pedagogically advisable. Appropriately, what is at stake in authenticity work, more than perceptions of a single learning environment, are professional person likewise as educational norms and relationships.

Turning to the discursive strategies involved in teachers' authenticity work, our findings signal that they tin be problematic. We want to emphasize, however, that the discursive strategies we observed in the classroom tin also exist seen in the rhetoric employed in major parts of the literature on educational actuality and that these strategies should not be viewed as synthetic by whatsoever individual instructor. Every bit pointed out by Hung and Chen (2007), the literature on authenticity risks "demeaning" higher instruction by assuming that in that location is a cohesive, "traditional," pedagogy and learning practice in academia that is uniformly misaligned with effective instruction. In a similar vein, Dishon (2020) points out that literature on educational actuality often assumes that there is a cohesive professional person do "out there" that learning environments can and, mayhap more importantly, should be modeled on (and thereby perpetuate). Nosotros question both the veracity and the consequence of such assumptions. First, we believe that they practice not exercise justice to the multitude of aims and practices pursued inside and outside academia nor to the diversity among students and professionals. Second, nosotros saw in our written report how such assumptions informed a relegation of students' critical reflections regarding professional person exercise and effective instruction, closing down opportunities for students to develop disquisitional thinking about their profession and education.

Given that authenticity piece of work can exist a double-edged sword, associated with both favorable and unfavorable consequences, where does this leave us? Is authenticity work always at odds with fostering critical thinking most the profession and instruction? If and then, does the end justify the means? Here, we agree with Philip et al. (2018), who make the point that ideological "convergence" is oft needed in teaching, but that "too early on ideological convergence, without acceptable engagement with ideologically expansive stances, constrains learning, only every bit as well early convergence on an engineering science solution frequently leads to junior products" (p. 185). Chua and Cagle (2017) offer a tentative style out of this dilemma, arguing that teachers should—every bit a minimum—make articulate to students that their silencing of alternative professional person and educational perspectives is a temporary and local bracketing, made in the name of efficiency. A more aggressive approach along these lines would be to draw inspiration from disquisitional pedagogy, which places importance on actively involving students in questioning dominant ideologies and practices (Breunig 2009). As such, critical instruction "encourages critical thinking and promotes practices that have the potential to transform oppressive institutions or social relations" (Breunig 2005, p. 109). Nosotros fence that the tenets of critical instruction can guide teachers in developing discursive strategies for authenticity work that are more uniform with fostering disquisitional thinking.

Implications for research

In the introduction, we drew attention to the empirical void surrounding teachers' authenticity work in higher education. Our report takes first steps to address this gap, and the findings betoken towards important directions for future research, forming a nascent research calendar on actuality work.

Regarding the content and structure of authenticity piece of work, nosotros run into ii main strands for future research. Outset, connected in-depth assay of classroom interactions could shed further light on what discourses are drawn on in authenticity work and how they are mobilized. Nosotros identified three discursive strategies involved in authenticity work: deficitization, naturalization, and polarization. In a similar report, Hsu and Roth (2009) outline how different "interpretative repertoires" are mobilized in motivating a science internship for upper secondary students. Nosotros additionally want to stress the importance of adopting a disquisitional perspective when studying any such discursive negotiations. 2nd, time to come piece of work may unveil how authenticity work varies beyond contexts. We studied authenticity work in a project-based software engineering form at a technical university. Actuality work should exist explored in other institutional settings (e.1000., in the context of medical or social work grooming) and for other pedagogical approaches (east.g., problem-based learning and service learning).

Turning to the ideological consequences of authenticity work, we believe there is a need for further research on the norms and relationships that are enacted through authenticity work, as well equally the affordances of authenticity work for disquisitional thinking. Recognizing that authenticity is co-constructed by whatever and all participants of a social practice (Peterson 2005), it is integral in such work to clarify how discursive resources and strategies introduced in teachers' actuality work are reproduced, rearticulated, and/or rejected by students. One of import direction for such analysis is the consequences of authenticity work for students' identity negotiations (Johansson et al. 2018; Pattison et al. 2020), including questions as to how students assess their ain abilities and how they accredit value to unlike aspects of their professional person practice— such as technologies, customers, and societal impacts.

Future work may also study consequences of authenticity work more broadly, for example, in terms of effects on student engagement and learning outcomes. Such piece of work may help tease out the role of authenticity work vis-à-vis the part of dissimilar "authentic" educational designs in bringing about certain effects. Of particular interest, here are studies comparing consequences of (ane) similarly designed learning environments where teachers put unlike emphasis on authenticity work and (2) different educational designs where teachers put like emphasis on authenticity work. Such studies could shed light on the fact that comparative studies of interventions designed to take a lower vis-à-vis college degree of educational authenticity have yielded inconclusive correlations between on the ane hand authenticity and on the other hand student engagement and performance (Chen et al. 2015; Hursen 2016; Radović et al. 2020).

Decision

This report breaks new empirical ground by exploring authenticity work in higher education learning environments. Taking departure in a view of educational authenticity every bit a socially constructed property of learning environments, our findings claiming the dominant view on educational authenticity in two important means. First, the findings illustrate that authenticity work can be usefully understood equally an ideological project and suggest that this project involves a renegotiation of both professional and educational discourse. This challenges the view that authenticity work simply seeks to address and change perceptions of learning environments. 2nd, the findings advise that actuality work tin can be a double-edged sword, bolstering the legitimacy that is ascribed to learning environments but stifling students' critical thinking about both their profession and educational activity. This challenges the more key view that it is inherently positive to strive for accurate learning environments. Based on our findings, nosotros invite teachers and researchers alike to adopt a more critical stance towards educational authenticity. More specifically, we invite (1) teachers to draw inspiration from critical pedagogy to develop discursive strategies for authenticity work that are uniform with fostering disquisitional thinking and (2) researchers to further investigate the affordances of authenticity work for critical thinking.

Data availability

With consideration taken to the anonymity of the respondents, total data and textile are not fabricated public.

Code availability

Not applicable

Notes

-

Because the term "authenticity work" is an import from management studies, it did not aid us in search for previous educational research. Instead, we searched Scopus and Web of Science for manufactures in which title, abstruse, or keywords included both one term indicating a focus on authenticity (authentic learning, accurate pedagogy, authentic assessment, authentic instruction, educational authenticity, authenticity in education, accurate education, authentic chore, accurate problem, authentic context, accurate science) and one term indicating a focus on teachers' influence on learners (influenc*, persua*, convinc*, negotiat*, rhetor*, discour*). The search was conducted nine February 2021 and yielded 309 results in Scopus and 223 results in Spider web of Science. We screened the titles, read abstruse of papers with relevant titles, and finally read full papers if the abstract was relevant. Because nosotros but found 1 study directly examining teachers' authenticity work, done in a secondary schoolhouse setting (Hsu and Roth 2009), we also conducted backwards and forwards citation searches for primal references emphasizing the need for teachers to engage in authenticity work (Petraglia 1998; Nicaise et al. 2000; Herrington et al. 2003; Gulikers et al. 2008; Hsu and Roth 2009; Woolf and Quinn 2009) but did not identify any additional relevant articles.

-

All names that appear in the paper are pseudonyms.

-

Although nosotros distinguish among several discursive strategies below, nosotros do non want to suggest that these strategies are deliberately employed by the teachers in the course. Rather, the pick of the term "strategy" reflects our analytical interest in the furnishings of certain patterns of language use. The teachers certainly did intend to shift some views on the course, just probably not the total discursive shifts and consequences nosotros highlight hither.

References

-

Alvesson, Thou., & Kärreman, D. (2011). Qualitative inquiry and theory development: Mystery as method. Sage Publications.

-

Andersson, S., & Andersson, I. (2005). Accurate Learning in a Sociocultural Framework: A case study on non-formal learning. Scandinavian Periodical of Educational Research, 49(iv), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830500203015

-

Atkinson, D., Okada, H., & Talmy, S. (2011). Ethnography and soapbox assay. In K. H. a. B. Paltridge (Ed.), Continuum companion to discourse analysis (pp. 85–100). Continuum.

-

Barab, S. A., & Duffy, T. (2012). From practice fields to communities of do. In S. Land & D. Jonassen (Eds.), Theoretical foundations of learning environments (2d ed., pp. 29–65). Routledge.

-

Barab, S. A., Squire, K. D., & Dueber, W. (2000). A co-evolutionary model for supporting the emergence of authenticity. Educational Technology Research and Development, 48(two), 37–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02313400

-

Barton, A. C., Kang, H., Tan, E., O'Neill, T. B., Bautista-Guerra, J., & Brecklin, C. (2013). Crafting a future in science: Tracing centre school girls' identity work over time and space. American Educational Inquiry Journal, l(one), 37–75 doi:10/gctkps.

-

Bialystok, Fifty. (2017). Actuality in pedagogy Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford University Press.

-

Blumenfeld, P. C., Soloway, East., Marx, R. W., Krajcik, J. S., Guzdial, 1000., & Palincsar, A. (1991). Motivating project-based learning: Sustaining the doing, supporting the learning. Educational Psychologist, 26(iii-4), 369–398. https://doi.org/x.1080/00461520.1991.9653139

-

Breeze, R. (2011). Critical soapbox analysis and its critics. Pragmatics, 21(iv), 493–525. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.21.4.01bre

-

Breunig, M. (2005). Turning experiential education and critical pedagogy theory into praxis. The Journal of Experimental Education, 28(2), 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382590502800205

-

Breunig, Thou. (2009). Educational activity for and about critical pedagogy in the post-secondary classroom. Studies in Social Justice, 3(2), 247–262. https://doi.org/x.26522/ssj.v3i2.1018

-

Chen, R., Grierson, Fifty. Eastward., & Norman, Yard. R. (2015). Evaluating the impact of loftier-and depression-fidelity instruction in the evolution of auscultation skills. Medical Didactics, 49(three), 276–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12653

-

Chouliaraki, Fifty., & Fairclough, N. (1999). Discourse in late modernity: Rethinking critical discourse analysis. Edinburgh University Printing.

-

Chua, M., & Cagle, L. Due east. (2017). Y'all can change the world, only not this homework consignment: The contradictory rhetoric of engineering agency. Newspaper presented at the 2017 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Indianapolis, October, 18-21.

-

Delamont, S. (2012). 'Traditional' ethnography: Peopled ethnography for luminous description. In Southward. Delamont (Ed.), Handbook of qualitative research in education. Edward Elgar Publishing.

-

Dingsøyr, T., Nerur, S., Balijepally, 5., & Moe, North. B. (2012). A decade of agile methodologies: Towards explaining agile software development. Periodical of Systems and Software, 85(6), 1213–1221. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.jss.2012.02.033

-

Dishon, K. (2020). The new natural? Authenticity and the naturalization of educational technologies. Learning, Media and Technology. https://doi.org/ten.1080/17439884.2020.1845727

-

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Polity press.

-

Gee, J. P. (2014). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. Routledge.

-

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures (Vol. 5019). Basic books.

-

Gulikers, J. T., Bastiaens, T. J., & Kirschner, P. A. (2004). A 5-dimensional framework for authentic cess. Educational Applied science Research and Development, 52(iii), 67–86. https://doi.org/ten.1007/BF02504676

-

Gulikers, J. T., Bastiaens, T. J., Kirschner, P. A., & Kester, Fifty. (2008). Authenticity is in the eye of the beholder: pupil and instructor perceptions of assessment authenticity. Journal of Vocational Educational activity and Grooming, sixty(iv), 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820802591830

-

Herrington, J., Oliver, R., & Reeves, T. C. (2003). Patterns of engagement in accurate online learning environments. Australasian Journal of Educational Engineering science, nineteen(one), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1701

-

Hsu, P.-L., & Roth, Westward.-1000. (2009). An analysis of instructor soapbox that introduces existent science activities to high school students. Enquiry in Science Instruction, 39(iv), 553–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-008-9094-9

-

Hung, D., & Chen, D.-T. V. (2007). Context–process authenticity in learning: implications for identity enculturation and boundary crossing. Educational Technology Enquiry and Development, 55(2), 147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-006-9008-iii

-

Hursen, C. (2016). The touch of curriculum developed in line with accurate learning on the teacher candidates' success, attitude and self-directed learning skills. Asia Pacific Didactics Review, 17(1), 73–86. https://doi.org/x.1007/s12564-015-9409-2

-

Johansson, A., Andersson, Due south., Salminen-Karlsson, M., & Elmgren, Yard. (2018). "Shut up and calculate": the bachelor discursive positions in quantum physics courses. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 13(1), 205–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-016-9742-eight

-

Jonassen, D., Strobel, J., & Lee, C. B. (2006). Everyday problem solving in engineering: Lessons for engineering science educators. Journal of Engineering science Pedagogy, 95(2), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2006.tb00885.x

-

Kreber, C., & Klampfleitner, M. (2013). Lecturers' and students' conceptions of authenticity in teaching and bodily teacher actions and attributes students perceive as helpful. College Education, 66(iv), 463–487. https://doi.org/x.1007/s10734-013-9616-10

-

Krzyżanowski, M. (2011). Ethnography and disquisitional soapbox analysis: Towards a problem-oriented research dialogue. Disquisitional Discourse Studies, 8(4), 231–238. https://doi.org/ten.1080/17405904.2011.601630

-

Lüddecke, F. (2016). Philosophically rooted educational authenticity as a normative ideal for education: Is the International Baccalaureate'south Main Years Programme an instance of an authentic curriculum? Educational Philosophy and Theory, 48(5), 509–524. https://doi.org/x.1080/00131857.2015.1041012

-

McCune, 5. (2009). Concluding year biosciences students' willingness to engage: Teaching–learning environments, authentic learning experiences and identities. Studies in Higher Education, 34(3), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802597127

-

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. 1000. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. SAGE.

-

Newmann, F. M., Marks, H. Chiliad., & Gamoran, A. (1996). Accurate education and educatee performance. American Periodical of Education, 104(4), 280–312.

-

Nicaise, M., Gibney, T., & Crane, M. (2000). Toward an understanding of accurate learning: Student perceptions of an accurate classroom. Journal of Science Didactics and Technology, 9(1), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009477008671

-

Pattison, S., Gontan, I., Ramos-Montañez, S., Shagott, T., Francisco, Grand., & Dierking, L. (2020). The identity-frame model: A framework to describe situated identity negotiation for boyish youth participating in an informal applied science education program. The Periodical of the Learning Sciences, 29(4-five), 550–597. https://doi.org/ten.1080/10508406.2020.1770762

-

Perkins, D. N., & Salomon, G. (2012). Knowledge to become: A motivational and dispositional view of transfer. Educational Psychologist, 47(3), 248–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2012.693354

-

Peterson, R. A. (2005). In search of authenticity. Journal of Management Studies, 42(5), 1083–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00533.ten

-

Petraglia, J. (1998). The existent world on a curt leash: The (mis) application of constructivism to the pattern of educational technology. Educational Technology Research and Evolution, 46(3), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02299761

-

Philip, T. Yard., Gupta, A., Elby, A., & Turpen, C. (2018). Why ideology matters for learning: A case of ideological convergence in an engineering science ethics classroom discussion on drone warfare. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 27(2), 183–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2017.1381964

-

Prince, M., & Felder, R. (2007). The many faces of anterior teaching and learning. Journal of College Science Teaching, 36(v), xiv–20.

-

Radović, S., Firssova, O., Hummel, H. Grand., & Vermeulen, Thousand. (2020). Strengthening the ties between theory and practise in higher pedagogy: an investigation into different levels of authenticity and processes of re-and de-contextualisation. Studies in Higher Education, 1-xvi. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1767053.

-

Ramezanzadeh, A., Zareian, G., Adel, S. M. R., & Ramezanzadeh, R. (2017). Authenticity in teaching: A constant procedure of condign. Higher Instruction, 73(2), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0020-ane

-

Reeves, S., Peller, J., Goldman, J., & Kitto, S. (2013). Ethnography in qualitative educational enquiry: AMEE Guide No. 80. Medical Teacher, 35(8), 1365–1379. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.804977

-

Roach, K., Tilley, E., & Mitchell, J. (2018). How authentic does accurate learning have to exist? Higher Education Pedagogies, three(1), 495–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2018.1462099

-

Schwaber, Thousand., & Beedle, M. (2002). Active software development with Scrum. Prentice Hall.

-

Shaffer, D. West., & Resnick, One thousand. (1999). "Thick" authenticity: New media and authentic learning. Periodical of Interactive Learning Research, ten(ii), 195–216.

-

Splitter, Fifty. J. (2009). Authenticity and constructivism in pedagogy. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 28(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-008-9105-3

-

Stein, South. J., Isaacs, G., & Andrews, T. (2004). Incorporating authentic learning experiences within a university class. Studies in Higher Education, 29(ii), 239–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/0307507042000190813

-

Strobel, J., Wang, J., Weber, Northward. R., & Dyehouse, Thou. (2013). The role of authenticity in design-based learning environments: The case of engineering education. Computers in Educational activity, 64(May), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.11.026

-

Sutherland, L., & Markauskaite, L. (2012). Examining the role of authenticity in supporting the development of professional identity: An example from teacher teaching. Higher Pedagogy, 64(6), 747–766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9522-7

-

Vaara, Due east., Tienari, J., & Laurila, J. (2006). Pulp and paper fiction: On the discursive legitimation of global industrial restructuring. Organization Studies, 27(6), 789–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840606061071

-

Wald, N., & Harland, T. (2017). A framework for authenticity in designing a research-based curriculum. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(seven), 751–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1289509

-

Wallin, P., Adawi, T., & Gold, J. (2017). Linking instruction and research in an undergraduate course and exploring student learning experiences. European Journal of Engineering Education, 42(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2016.1193125

-

Wedelin, D., & Adawi, T. (2015). Practical mathematical problem solving: Principles for designing small realistic problems. In M. A. Stillman (Ed.), Mathematical Modelling in Didactics Research and Practice (pp. 417–427). Springer.

-

Weninger, C. (2018). Problematising the notion of 'authentic schoolhouse learning': Insights from educatee perspectives on media/literacy education. Research Papers in Education, 33(2), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2017.1286683

-

Woolf, N., & Quinn, J. (2009). Learners' perceptions of instructional design practice in a situated learning activeness. Educational Applied science Research and Development, 57(ane), 25–43. https://doi.org/ten.1007/s11423-007-9034-9

Acknowledgements

Nosotros would like to thank our respondents for their participation and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Chalmers Academy of Technology.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Ideals declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This commodity is licensed under a Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, equally long as you requite appropriate credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other tertiary party textile in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the cloth. If material is not included in the article'south Creative Commons licence and your intended employ is non permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission straight from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/four.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hagvall Svensson, O., Adawi, T. & Johansson, A. Actuality work in college educational activity learning environments: a double-edged sword?. High Educ (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00753-0

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1007/s10734-021-00753-0

Keywords

- Authentic learning

- Authenticity work

- Technology education

- Ethnography

- Critical soapbox analysis

- Critical thinking

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10734-021-00753-0

0 Response to "Thick Authenticity New Media and Authentic Learning Review"

Postar um comentário